El Anatsui: Music, Change and Re-Invention

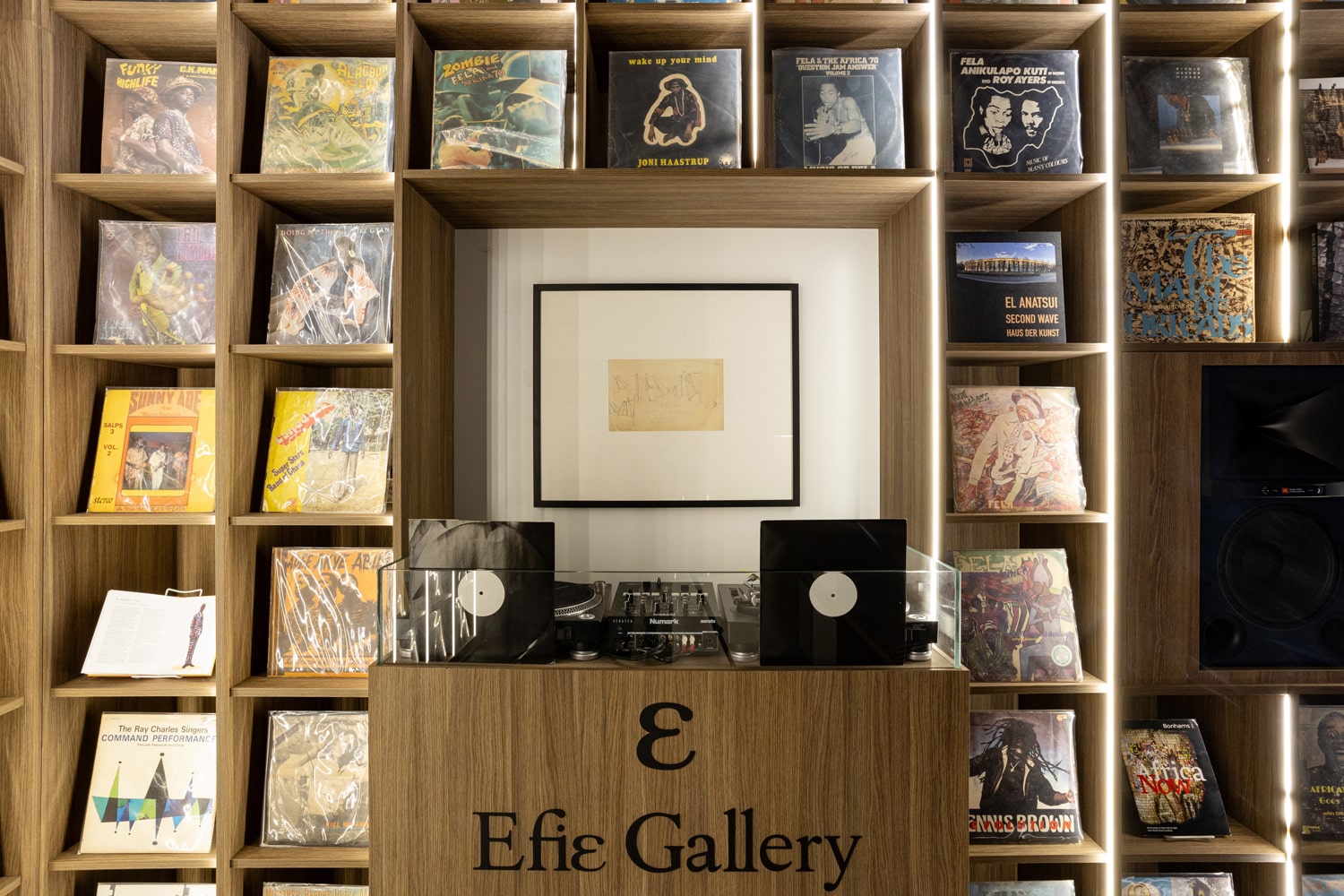

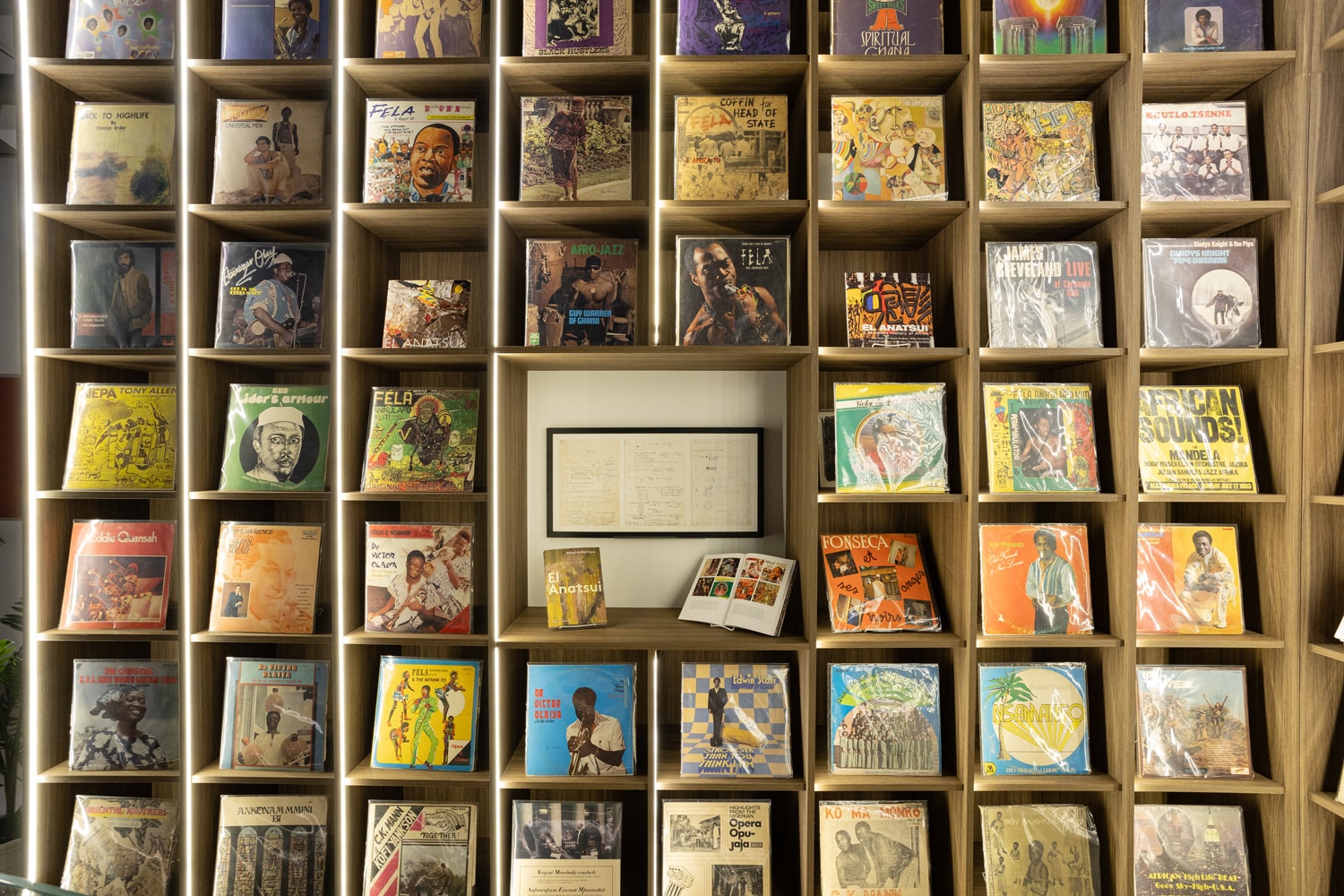

This exhibition presents a unique showcase of the pioneering artist El Anatsui’s personal vinyl record collection. Revealed to the public for the first time, this collection of over 70 records provides an exclusive insight into the cultural influences that have played a significant role in shaping the artist’s remarkable career. Among the featured records are those by notable artists such as Johnson Adjan & His Opiri Group, Aretha Franklin, Guy Warren, Vicky ‘Manze Onuba and Fela Kuti. These records, curated from the artist’s personal collection, will be exhibited alongside some of his early sketches and literature.

El Anatsui: Music, Change and Re-Invention - Written by Kwame Mintah

“I have always believed in the element of change, I don’t think my work should be the same thing anytime you see them, they should be changing.”

– El Anatsui

Change is a theme that is central to the work of El Anatsui. This is captured in the free-form nature of the bottle cap works, which can envelop a singular wall in a multitude of ways. In the ambiguous titling of the works that often have multiple meanings, like Detsi (2008-2021) an Ewe title signifying the prominent red hues of the work, which can mean soup, stew, the palm of a hand or a palm tree. As well as in his woodworks, where even in working with a medium that has an inherently rigid structure, through the system of panelling, these works remain fluid as their arrangement is interchangeable. Anatsui alludes to the notion that the theme of change is musical in nature.

“My work has a lot to do with time, It’s not something which is absolute, just like in music you carry sound through time in order to create music and I think in that sense the two are similar. Indeed a musician is an artist, there’s no difference between the two of them, we all compose. In my case since I have been working with the idea of the non-fixed form or dynamic form, in which the same piece can go through several manipulations and change formats throughout time; what you see it saying at a particular time is different from what it will say another time, or what it has said in the past.” – El Anatsui

Moving beyond the analysis of the theme of change in Anatsui’s work, the influence of music remains evident. One could argue that music is a foundation in which Anatsui’s entire visual language has been harvested upon. Through discussion we learn that this foundation was laid early on in Anatsui’s childhood.

“I don’t think there has been a time that the two (music and visual art) have not been together with me, I didn’t transition. The two have always lived with me right from childhood when I took a particular interest in music. I think that growing up in the Mission House brings you in contact with music, well, the kind of music that you hear in the church and the music you hear in the traditional local society. I saw the differences between the two, one using harmonies which tend to use all the notes of the scale and the traditional music which tends to use 5 notes in the scale and so the (traditional) harmonies are different, using what musicians call consecutives, travelling together, one is high and the other is low, parallel to one another, something I have taken particular liking to very much. I have seen a couple of African musicians who have gone to music schools abroad and try to use it. I think Fela uses it in his harmonies; he doesn’t use the Western harmony, but the African one.” – El Anatsui

‘Seeing the differences’ in music can be illustrated when we look at the timeline of West African music, as we are able to see how and why these differences were fostered. From as early as the 19th century Osibi has had a presence in West Africa. This up-beat form of traditional music was historically played under the moonlight in a group setting, originating from recreational maritime influenced guitar and accordion music of Fanti fishermen in the 1900s. The 1920s saw the birth of Highlife at height of British colonialism. This music was a fusion between Osibi and western jazz melodies, which incorporated the use of foreign instruments, with the first highlife song ‘Yaa Amponsah’ being recorded in London by Jacob Sam (Kwame Asare) & Kumasi 3 in 1928. At arguably the height of Pan-Africanism, between the 60s and 70s, highlife music went through a renovation of sorts, where West African musicians saw a need to innovate. Artist Dr. K Gyasi originated the sub-genre Sikyi-Highlife which incorporated the electric organ into the Highlife sound, whilst other musicians, notably Nana Ampadu and African Brothers with their record Odaano Traditional Highlife (1976), focused on re-indigenising the genre, which uncovered the historic Odaano style paired with 20th century instruments. In this same period Fela Kuti also birthed Afro-Beat, an entirely new genre which took Highlife and infused elements of funk, soul and jazz into the sound. This timeline is crucial when looking at the work of Anatsui as the way he discusses the progression of African art, and the impact said progression has had on his own practise, closely mirrors that of the progression of West African music over time.

“It is not that the use of found objects is new to art produced in the African continent. I think it’s something that has been there right from the beginning. We’ve only had an incidence of art schools coming in from the West, interrupting this and instituting in its place the use of the so- called “traditional” (art) materials, like when I was in art school, we were handling plaster of Paris and such stuff which didn’t have any relationship to the environment. I thought that in traditional African art which we got to know about later on, they would use things that were occurring in the environment, combining things like wood, skin, feathers and so on and so forth. In other words, they source their materials or their media right from around them. We have had a long period of art schools having introduced this idea which took us rather back; and so, what I think I’m trying to do, me and some colleagues, is to kind of bring back this kind of attitude, the attitude that in the past would lead us to work with these unusual materials. (Unusual materials from a foreigner’s context, yet usual in an African context)” – El Anatsui

Here we learn of Anatsui’s desire to engage with the African environment and create “African” art. Whilst the definition of music, much like that of artwork, is challenging to define, when we localise the parameters of the question does the same hold true? When we discuss African, Asian, European or American art, often the way in which an artwork is characterised lies within the origin of the creator. However, when we draw parallels between visual art and music, we are able to seek something further. For when characterising a musical ensemble, the active agent is the music itself as opposed to the individual. if an Asian musician was to make an afrobeat piece, despite the origin of said individual, the characterisation of this song would be unaltered, it would remain afrobeat, as exemplified by Japanese band Ajate and their catalogue of Afrobeat music.

Distinguishing between genres and sub-genres is focused on the way in which the music is structured, encompassing elements such as: musical scale, harmony, melody and rhythm. Anatsui, similarly to West African musicians, who reinvented Highlife through a process of Sankofa or in the case of Fela Kuti created an entirely new genre (afrobeat), questioned whether this same structural system of thought could be applied to art and if so, what would inform the structure? What is the visual art equivalent of a musical scale, harmony, melody and rhythm? To Anatsui the answer lies in the medium. How something is created is as important as who is its creator.

“I was a teenager when my country became independent. The idea of independence brought in this sense of euphoria, and well, we thought we were free and therefore we were going to do something great. Colonialism covered your face with a veil and now the veil is removed, what do you do? You look around and see. In most parts of Africa at the time there were movements or syndromes, of going back to look at some of the things that were there before the colonial project started and trying to learn things from the past. In Ghana I remember we had a Sankofa Syndrome, Sankofa means going back and picking, it is something like introducing the sense of historicity into one’s life; you don’t just keep moving forward but go back and look at what you did in the past and try to use it as a way of moving forward.” – El Anatsui

For an artist who always maintained a predilection for the objects of his environment, he was himself one, moulded by the volatile forces concomitant with colonialism and independence. If change has permeated his works, so has the tendency to draw from the reservoir of techniques, music and philosophy that was suffocated under colonial tutelage and re-visited in the cultural rebirth that followed. Here we find the great duality of his pieces, the imprint of both personal and collective experience and ingenuity. El Anatsui’s art, as he suggests, conveys disparate meanings in changing times, but its legacy will be that quality that is anathema to the artist himself; permanent.